MURMURATION

“And I? I drink, I burn, I gather dreams. And sometimes I tell a story.”

“What do we glean from the stories of other women?”

Terry Tempest Williams, When Women Were Birds

In the summer of 2018 while I was watching the senate confirmation hearings, I started to think about ways that women are not heard or, by choice, stay silent and wait. I wanted to put together a project that would build into a kind of chorus of collective ideas and voices to counteract the moment of hopelessness. Days later, I fortuitously discovered the book When Women Were Birds by writer/environmentalist/activist, Terry Tempest Williams. The opening passages are blank, a reference to three shelves of empty journals inherited from her mother, discovered only after her mother had passed away. These unfilled pages also represent an invitation to imagine/re-imagine the words left unspoken or the stories that can be told moving forward.

This exhibition series, Murmuration, unfolded over the course of the academic year of 2020 beginning in January and ending in December at the New Image Gallery at James Madison University. It was designed to counter expectations of a conventional exhibition series. Working in three groups of three individuals, each new installation reconfigured and was added to the previous, building in complexity as the series evolved, creating a harmony of imagery and narrative from nine women artists from across the state of Virginia. The series then concluded over the course of the fall semester 2020 in the same way it began, but in reverse: each of the groups of three emptied and reconfigured the installation space as the collection once again dispersed.

-Rebecca Silberman, Curator's Statement

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS

Variation I: Nava Levenson, Martha Saunders, Rebecca Silberman

Variation II: Corinne Diop, Julia Merkel, Kristin Skees

Variation III: Christa Bowden, Dymph de Wild, Rosemary Jesionowski

MURMURATION, Variation I Nava Levenson “Birds remain my compass points. Wherever I am, the winged ones orient me: a red-winged blackbird in a marsh; a willet on a beach; a kestrel hovering in a field.” - Terry Tempest Williams “Field Guide to Compass Points” is an assemblage of voice; a chorus within a larger chorus, a glimpse into the memory and story of women. As Tempest Williams’ mother’s journals where blank; my mother keeps all her sentimental objects in white cloth bag stowed away. Objects, rich with history and sentiment, have always been my compass points. Objects are resource; objects are home. The inability to let go contrasted with ability to hold on and remain accountable for a collection of objects who otherwise float among our planet is at the root of my practice. This wallpaper is a collection of objects of maternal sentimental value to myself, my mother, and my collaborators. They stand together occupying both wild and domestic ecologies. Scattered among the scape are also handkerchiefs from A Napkin A Day: February 2019. This project is a ritual and collection of personal mess within my domestic ecology. These spatterings, spills, and residue beg us to consider the site specificity of dirt as an object defined by its context. Martha Saunders Collaborations spawn unknown forms from multiple imaginations, creating a force that hopes to reveal another way. Murmurations, a physical manifestation of many voices, become a large reaction to be reckoned with. Visions combined strengthen and clarify to culminate into a unified song. There is a Greek myth where a woman’s voice is taken away and her ability to speak stolen, so that she will not reveal the truth of her experience. Banished into a concealed life by a king, she spends years translating her rage, sadness, and grief into sewn effigies that replicate the conflict that determined her fate. As this tragedy progresses into scenes of confrontation and acts of revenge, the character in the end changes into a bird, leaving the listener of this tale with the hope of transformation. Rebecca Silberman The last Carolina parakeet, the only North American parrot, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, almost exactly 100 years ago. One night I dreamt that there were nocturnal birds with feathers of vantablack, the darkest substance known. They couldn’t be seen, so they couldn’t be destroyed; they were adapted to human exploitation by evolving into “Invisible Birds.” The fabric imagery for this project is based on the “Invisible Bird” series, which made use exclusively of expired tintype plates—up to ten years beyond usability. The setting is a cleared plot of land close by my home; this “stump garden” serves as the backdrop to handmade cloth backdrops depicting flocks of birds, one fabricated from small effigies and another photographed as an exploding murmuration. The plates have been translated into a new generation of gossamer backdrops and layered together with the originals depicted in the tintypes, in a potentially infinite cycle of creation and re-creation. The knees featured in this installation are a life study from a plaster statue my grandmother, Sarah Gettleman Silberman, made of a somber classical work influenced by Italian funerary figures. I had the hand resting above the knees for years as well, but only made the connection that they were from the same figure study working on this project. The pedestal was found down in the woods when we moved to our building twenty-five years ago. These elements for this project about women and stories and generations, voice and silence have emerged out of a bank of advancing smoke in my mind. Why did I place the knees in the burned up sink pedestal? I have no idea, but it fit like they were made to go together. And down the hill in the rain just days ago I found a heavy moss-covered block with an open cavity, like the cap of a chimney stack. It holds the pedestal perfectly and another line in the tale is written. There is still so much to uncover, discover and recover. Our story is not over…

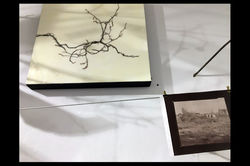

MURMURATION, Variation II Corinne Diop Red Wings, 2019 A flash of red caught my attention as I walked towards the door. Red bird wings were flattened and lifeless on the ground, yet were spread open in symmetry as if recalling the graceful flights of an earlier existence. Aside from a few shreds that still clung to the wings, the rest of the bird was gone. No more cheerful singing and trilling. Instead, the quiet stillness allowed me to closely examine the exquisitely tiered wing structures and the nuance of the darker and brighter shades of red feathers. I felt a compulsion to preserve this beauty discovered on a bleak day. I found a question posted on Quora: “What does it mean to find a dead red cardinal at your doorstep?” One responder suggested the event should be interpreted as an awake dream, with the bird representing intuition or spirit and its death representing “the new that wants to come”. Red Wings is a series of photographs and mixed media that examines this question. Julia Merkel Absent, 2017 Artists’ books are a hybrid form that allow for great flexibility with content, materials, and imagery. “Absent” is from the body of work “Absence/Presence: Drawing from Grief” created after the death of my son. There are no words; there is no text written within the pages. The pages themselves are torn from tar paper and sewn into cherry boards with long tendrils or guts spilling out from the pages and meant to evoke the shock and expurgation after a sudden loss. “Absence” is one of a pair. “Present” is its opposite and made from creamy white Arches drawing paper. The tendrils torn from the pages of “Present” float out from the boards and curl upwards like smoke. “Murmuration” is a three-volume set of artists’ books created specifically for this 2020 exhibit. Abstracted silhouettes of terns are used in movable or “pop-up” formats alternately exposed or hidden when the boards of the books are open and closed. I am particularly drawn to bird imagery as a symbol for the spirit. Byzantine angels were painted in a jumble of three sets of frenetic wings--making this set of three books with their boards outstretched an acknowledgment of an iconoclastic past. Likewise, the tombstone shapes of the boards are intended as an homage for an endangered bird species and a warning for our future. The Roseate Tern is not yet extinct which leaves room for hope. Krisitn Skees Maternal Memory, 2020 One need not write in order to have a voice. A mother speaks to her children through the generations. Terry Tempest Williams, “When Women Were Birds” “Maternal Memory” explores what it means to understand and create a personal history through photographs. At its heart is the knowledge that women have often been the caretakers of family albums, and family history, and how this creative force is so often taken for granted. As a daughter, I pored over my family photo albums, seeing my grandmother in her youth, meeting her as I would never know her in my own present moment. I constructed my own memories from photos of me running through a backyard I barely remember, with a dog who was given away when I was three. I learned history through these objects. From yellowed, cardboard mounted baby grandmothers. To sleek, squared teenagers in bobby socks, black and white with white scalloped borders. To myself in red overalls, faded colors, rounded corners, still with a smell of musty processing chemicals. To saturated, glossy 4x6 little brother riding a bike for the first time. As a photographer, I come back to these images and understand them as meaningless relics of a shared cultural history. They are both the foundation of my identity, and they are nothing to the world outside my family. They were curated by mother and grandmothers, with carefully written captions, penciled dates and cursive names found on the back. They are as ordinary as the flea market box of nameless images I sift through each week. As a mother, I continue to create my family through photographs, as did my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother. To memorialize, carefully capture, and ultimatelyreconstruct my family’s history. It is simultaneously the most meaningful work I’ll make and the least exalted. “Maternal Memory” is created from my personal family photos, past and present, rephotographed as polaroids, reconstructing them into a different time, a different form. And like a murmuration of starlings, the memories flock together, pushing, shaping, reforming, until the singular gives way to the whole.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |

MURMURATION, Variation III Christa Bowden Growing up in the American south, I have always felt a deep connection to home, place, and nature, and the way that these things intertwine like overgrown muscadine vines becoming part of an aged tree. I spent most of my time outdoors as a child, and have always felt the most at peace in nature. When I was a baby, my parents realized that when I cried, they only had to take me outside and I would stop crying. The connection of place and family are inextricably bound together in my work. When I am walking in the woods seeking my subjects, I can’t help but think of my grandmother collecting native plant seeds and specimens for her garden, or my mother identifying which plants are edible and which must not be touched. It is these things that I have in mind as a gather my subjects like a collector. Often, I take these specimens from their existing place to isolate and photograph them with my flatbed scanner. By this method, I am able to visually evaluate these subjects and how they serve as metaphors and connecting my past to present, place to people. Dymph de Wild One day, at age eight, I was walking home from school and suddenly noticed I was being followed by an enormous crow. Unexpectedly the bird flew in closer, dove down and veered just over my head, almost touching my hair. When I arrived at the house, the crow was waiting for me on the roof of the garage. As soon as I opened the kitchen door, it spread its wings and aggressively tried to fly inside with me. A loud, hoarse scream escaped from the crow’s throat that sounded like an old laughing witch. Then it flew off, fearless. Silence. I reached into the pocket of my coat and felt for my gelukspoppetje (small good luck doll). I had survived the attack. Over the years, my interactions with crows have continued. When I was visiting the Netherlands in the summer of 2018, I came upon a field with hundreds of scarecrows intended to commemorate the 800th anniversary of the town of Oisterwijk. There was great thematic variety: Some were primitive, some more sophisticated, some looked human, and some were clownish, yet all together they seemed ominous and rather threatening. Since then, I have found myself building my own varieties of decoy creatures that not only protect me from crows but they can embody social and political commentary. Rosemary Jesionowski My work has long been about human relationships to place. How do these relationships define and sometimes change us? In the fall of 2018, I set out alone to travel across the United States on a three-month photographic road trip. I would capture the landscape on film and make albumen silver prints (a photographic process popular in the mid-late 19th century) along the way. I envisioned myself following the proverbial path of photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan with his darkroom on wheels and Eadweard Muybridge with his mammoth plate camera documenting Yosemite. I created a modern equivalent of O’Sullivan’s portable darkroom- a custom built cabinet to fit perfectly in the hatchback of my Subaru, with compartments for chemistry, paper, and equipment. I outfitted myself with a monorail view camera and several lenses. My route took me through sacred places that are personally and/or culturally significant. I drove from Rochester, NY, through the Badlands of South Dakota to my birthplace at the base of Mount St Helens. I meandered down the Pacific coast, dipped in to Yosemite and then headed inland over the Rockies to my childhood playground in Colorado. I sped through Texas to land in Louisiana, a place I called home for a bit. I photographed all of it. As I drove, I spent a lot of time thinking about my place in the history of photography. While the medium has been much more accessible than say, painting, to women throughout its short history, this particular arena of photography has always been (and is still) vastly dominated by men. Perhaps this is because wandering out into the land takes a certain sense of adventure that girls so frequently are not encouraged to explore as children, or maybe it’s the physical demands of carrying a camera (though I do know of several women who are working in the landscape with significantly larger cameras than the one I use). What does it mean to be a woman conquering the landscape? I certainly don’t feel as though I have conquered it, more so, I feel reclaimed by the land and the places that are significant. I have a romantic relationship to place and landscape. Mount St Helens is my mother, Pikes Peak is my father, and the Gulf Coast is my lover. This romance with the landscape is largely why I chose to print this body of work as albumen silver prints. They have an inherent romanticism to them. My images as albumen prints are tangible and yet fantastic. They represent some sort of reality, but it is certainly a skewed reality. The images are of both place and time, yet… they are timeless. One of the most beautiful aspects of an albumen print is its luminosity. This glowing quality comes from the fact that the image itself is suspended in egg white above the surface of the paper. Light passes through the albumen layer and bounces off of the paper, giving the image subtle backlighting. This is not lost on me as I am in the field, under my darkcloth, watching the light, thinking... about place, about time, about history.